In the villa, we meet the shell-shocked nurse, Hana, as she – heedless of danger – cares for the enigmatic patient burned beyond recognition or hope, who might or might not be English.

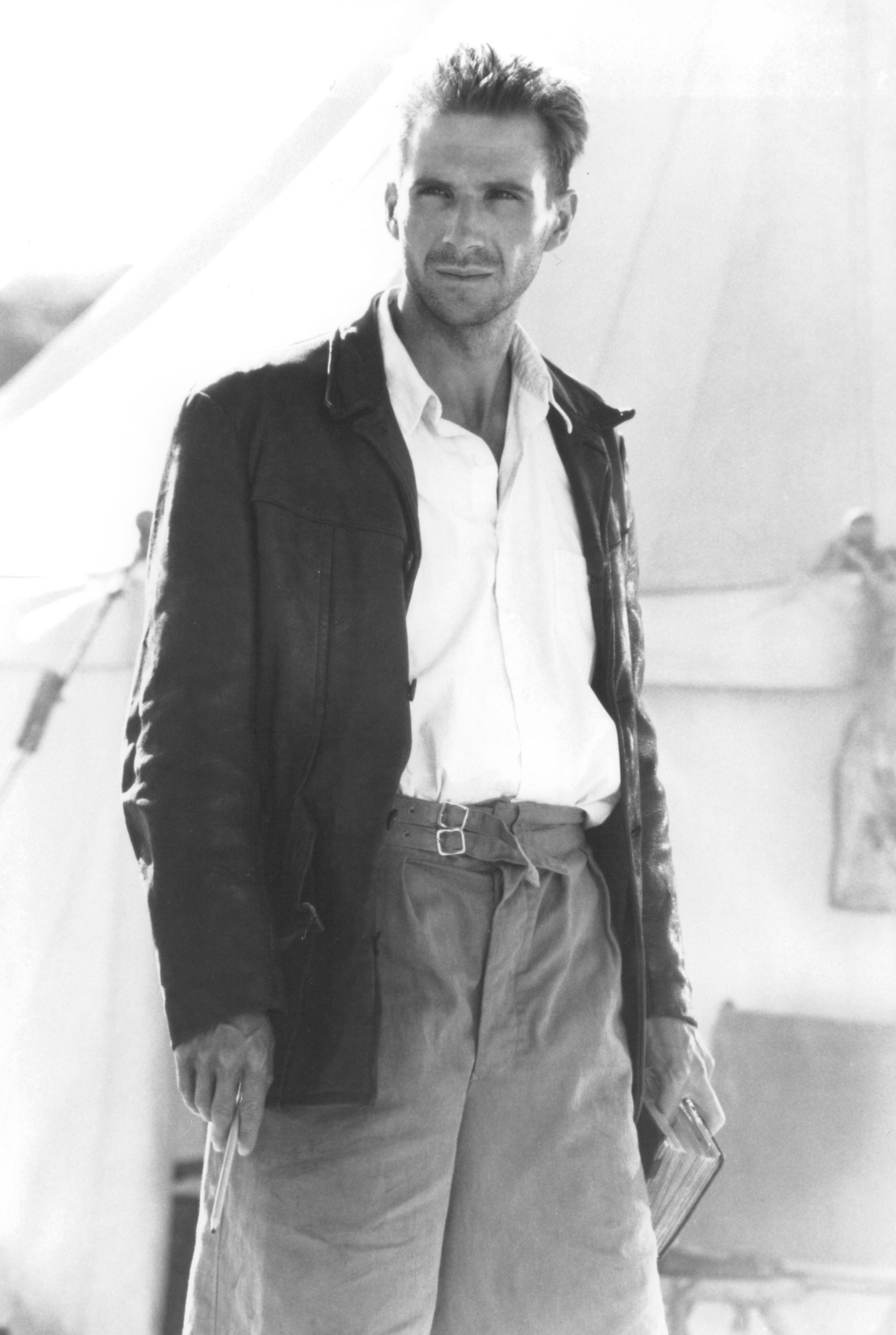

It is a beautiful story which creates a romantic setting out of a ruined Italian villa booby-trapped by the mines of the retreating German army, and juxtaposes it with the pre-war heroic age of discovery in the harsh deserts of Egypt and Libya. In this tale of four people damaged by the loss of innocence that inevitably accompanies war, Ondaatje has woven fragments of their past lives into their uncertain present as they themselves reveal it (as, in life, we do). Well, there are readers who like things to be straightforward (as if life is like that) and there are those who enjoy a carefully constructed artifice that gradually reveals the complexity of characters and events. I didn’t read much of this criticism (too depressing! too inane!) but I got the impression that these readers disliked having to ‘put together pieces of a jigsaw’. So you can imagine my astonishment when I saw some consumer reviews that claimed to have hated the book, dismissing it as pretentious or frustrating. It’s an enchantment, one that made it very difficult for me to tear myself away from it. The English Patient won the Governor General’s Award in Canada and shared the Booker Prize with Barry Unsworth’s Sacred Hunger in 1992. Perhaps that was because she too had a sense of perspective about human life that came from a love of wild, desolate places, indifferent and unforgiving… My own mother is the only other one I know ever to so perfectly explain the sense of living for the fragile moment during the Second World War. As I lost myself in the pages of The English Patient I could see the thin, taut faces of the characters as they were in the film, and I could see how perfectly the adaptation and casting had captured the brittleness of the world they inhabited. It’s a different experience, reading a novel after seeing the film first.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)